EVA KMENTOVÁ: ŽENA NA SLUNCI | WOMAN IN THE SUN

EVA KOŤÁTKOVÁ: ŽENA V BEDNĚ | WOMAN IN A BOX

curated by: Edith Jeřábková

exhibition architect: Dominik Lang

22| 9|- 16| 11|2018

hunt kastner is very pleased to present this very special joint exhibition of work by Eva Kmentová (*1928-1980) and Eva Koťátková (*1982), curated by Edith Jeřabková, and in cooperation with Dominik Lang as the exhibition architect. Special thanks go out to the estate of Eva Kmentová, who has so generously contributed with loan of work and access to archives, and to the other lenders: Prague City Gallery and The Jan and Meda Mladek Foundation at Museum Kampa.

The exhibitions Woman in the Sun and Woman in a Box are already linked by their titles. However, it was not our intention to frame the group exhibition of Eva Kmentová and Eva Koťátková. When looking at the entire work it is not clear if there is only one or two artists. But we only want to connect the work of both artists in the places where it actually connects, not to violently create contexts. We wanted to leave their individual autonomy intact. Of course, it is tempting for us to look for parallels in their work and we easily find them on various levels, but we must not generalize. About Kmentová, the theoretician and curator Ludmila Vachtová wrote that, “She was a great friend, but bilateral relations suited her temperament more than a group consciousness. She went her own way. With absolute openness she accepted each new subject and rejected influences. She enjoyed transformations. Eva’s work differed more and more from what was arising in the sculpture workshops of her generation. In her own studio in Žižkov she tried out all modalities of solitude and independence. It pleased her very much.”

Eva Koťátková can be similarly described (as well as several other female artists, of course) because her work at home or in the studio is very important for her despite the fact that she is constantly moving around the world. She is interested in the ever-present, consuming work of other artists and is even compulsive about it; these are often self-taught, naive artists as well as those who were diagnosed as mentally ill by society. Art that is completely undetached from the artist creates unalienated work, which, we believe, brings themes flowing from a constant process of arising that is non-speculative and inexhaustible. These themes, even though they arise at the margins, have their own effect at the moment when they are brought out into the daylight, into the public space. Even though they are not intentionally political, they are innately critical and reflective, and even through time, which renders many works silent, these works do not end up as merely decorative objects. This has already been proven with the works of Eva Kmentová, which were created under circumstances that are different from those today (post-war, circa 1968, the period of normalization) and are still able to communicate. We have therefore exhibited works from various periods of her creation in this exhibition.

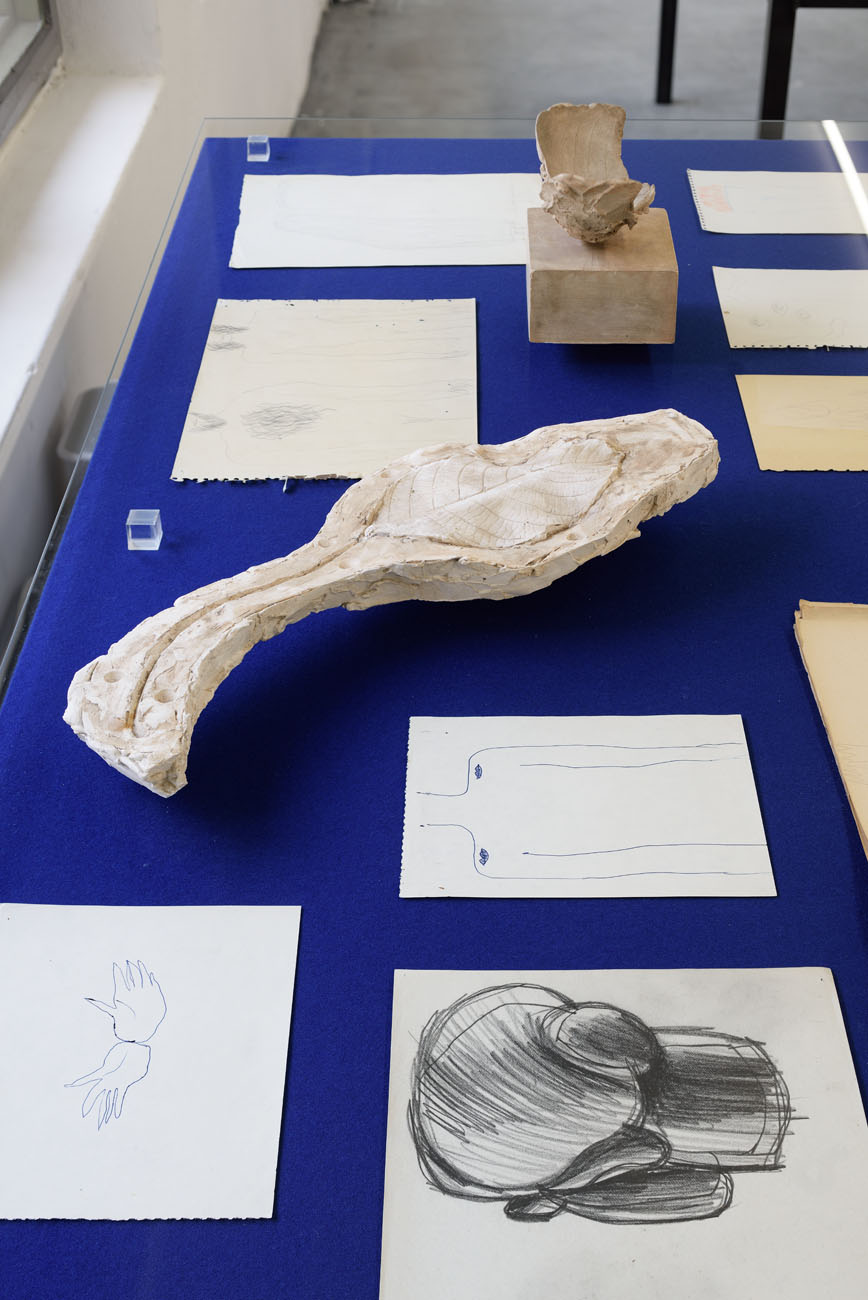

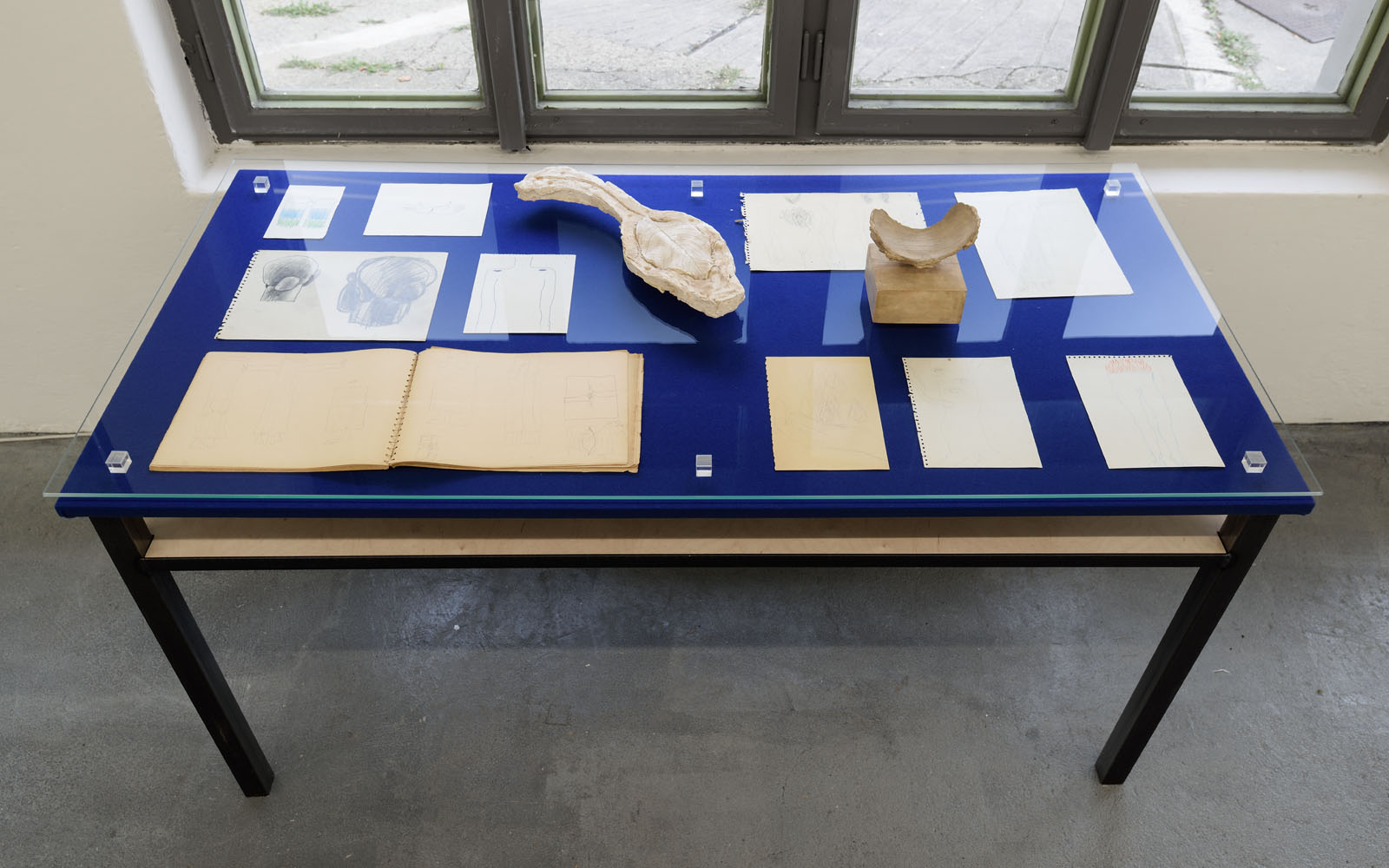

The studio is a place that interests us. It is the border between where something is created in isolation, which afterwards comes into the light of the world as a public object, and the conception of the exhibition emphasizes this. The gallery space behind the courtyard is a kind of studio, and an allusion to the studio of Eva Kmentová in Kalinince, where cement reliefs were also installed in an exhibition on outdoor walls (where they hung for many years). I am very happy that the exhibition’s architect – in the very broad meaning of the term “exhibition architect” – was the artist Dominik Lang. I wanted people to be able to walk through the exhibition and make a connection between the separate spaces of the gallery, the external and internal spaces to create a parallel with the internal work and its impression on the outside and vice versa. Dominik created this artistic concept for the exhibition, which importantly connects the interior and exterior with one long wall and other elements which straddle the border of individual works and the architecture of the exhibition.

Perhaps it is too strong a parallel, but both of the artistic couples, that is, Eva Koťátková and Dominik Lang, just like Eva Kmentová and Olbram Zoubek, break the stereotypical gender imbalances between male and female artists, but without reversing them, either. Unlike the married couples Jiří and Běla Kolář or Juraj and Maria Bartusz, neither of the Evas was, or is, overshadowed by their partners. This is necessary to say, especially today when such things are increasingly discussed among us and there has been wider reflection on feminist studies. I am therefore pleased that at this exhibition we can also openly introduce the partner cooperation of Eva and Dominik. One question is: how did Eva Kmentová feel being a part of this society of predominantly male sculptors, artists, and workers as we see in family photographs from her archive. Did she have to ‘show her muscles’ and cleverness more in order to be recognized? Ludmila Vachtová writes that Eva Kmentová felt comfortable being in the company of strong artistic couples, which is a kind of anomaly in post-war times and even in later periods. But how would today’s female artists feel in such company?

But if this exhibition discusses feminism, then it does so more by expressing the world of women, which is a significant theme throughout the work of Kmentová and Koťátková. It is certainly not a coincidence that Kmentová repeatedly depicts women and things connected to their world. Woman in a Box, in its many variations, and Woman in the Sun, at first glance, express an internal conflict of the ordinary, modern woman. But is this really the case? Are not boxes ever-present objects that surround the female sculptor – a box for clay, for tools, as a pedestal, or as furniture that a female artist is constantly moving around, on which she relaxes, contemplates, or converses with colleagues in her studio? Is it not the expression of the material essence of sculpture that Kmentová later overcomes by leaning towards conceptual expression and an emphasis on procedure? Woman in the Sun is hardly just a woman sunbathing. The exposure of the female body to sunlight certainly has more symbolic meanings interwoven with the prosaic ones since Kmentová actually grew up and lived close to nature, and which for her was always a source of inspiration, an aid for expressing her feelings and thoughts. Woman in the Sun could also be a woman of tomorrow, a sci-fi woman who unites her powers with the sun, one who does not only have to fulfill a romantic idea.

The box for Eva Koťátková is, on the other hand, a symbol of enclosure, imprisonment, but also of safety, from where it is possible to observe the world and have her own thoughts. Eva Koťátková’s Woman in a Box and Woman in the Sun seems to be a sign of how the female body is used in many cultures, even modern cultures – as an object which is placed into a box or exposed to the sun, enclosed in a home or representing the idea of natural forces. Woman in the Sun and in a Box can be, according to Koťátková, a metaphor for a female artist who has succeeded in getting into the light and conversely for those who voluntarily remained hidden in their studios or were swallowed up by caring for their families or simply forgotten, present only in the historical archives or not even. Woman in a Box may depict a woman who is not allowed to, or does not know how to, engage politically in public. In the exhibition, Koťátková has depicted a woman who always sits at home, reading the daily newspapers, making clippings and sending these back into the flow of the day, thus indirectly communicating with a world which she knows only from second-hand information and which is separate from her. She is probably thinking that all the news is about her, that the whole world is interested in her private life. She identifies with some news more and with some less. This woman says “my feelings are public matters” and then enters the public space where she sees a sphere full of individual bodies like hers and the complexity of the world stuns her because she was not aware of it. She is looking for a public forum to share her emotions. The headless woman wants her head back.

Finally, however, the box can also hide a secret within itself which, of course, is not to draw a parallel with a woman! And it can also be a place where we are able to store our wishes and desires if we are not able to express them in everyday life. It is both a psychological and a mythical idea. For Eva Kmentová, who is the author of the infinite and open work Box of Miracles, this box has a double meaning – it creates a society of participants, who were friends, acquaintances, and family members, and who were also conceptually engaged with the results and who wanted to unite intelligence with a more active position which would bring about a better society. Kmentová changed her mind about this approach when she was very ill and was ‘imprisoned’ in a hospital where no visitors could see her, not even through a window. The box is thus also a hospital room full of painful bodies. A similar conceptual work, of which there are more in her complete works, is untitled (Hands) from 1976-79. She traced, cut out and collected outlines of hands of family members and people she knew, which she exhibited in her studio in Stodola. Each hand has a name and is freely placed in a glass bowl with a lid. The family continued adding to this work even after Kmentová’s death. The box can therefore also represent socially connected people and things. Her notes in the family journal from March 1969, concerning the work Stopa, show that she wanted to strengthen the engaged component in art (which was probably not easily accepted in the male society of sculptors, but was nevertheless appreciated by Jindřich Chalupecký who commented: “This is not art anymore; that is now completely clear. Perhaps it could be described as an expression from the world, a feeling of the ordinary that should be more intensively perceived.”)

We have decided to revive the Box of Miracles and continue with Eva Kmentová’s idea by inviting exhibition guests and visitors to write a miracle, wonder or wish on a piece of paper and to place it into the box at the exhibition. We also wanted to contribute to these miracles ourselves in the form of several activities which will play out in a large room-sized box : with the magic of Jiří Kovánda, with female magicians, and by reading out the collected miracles with Eva Kmentová’s family and friends. This room sized Box of Miracles, painted with a relief of a hand, was artistically conceived by Dominik Lang and based on a sketch that Eva Kmentová drew on the back of a letter in 1976.

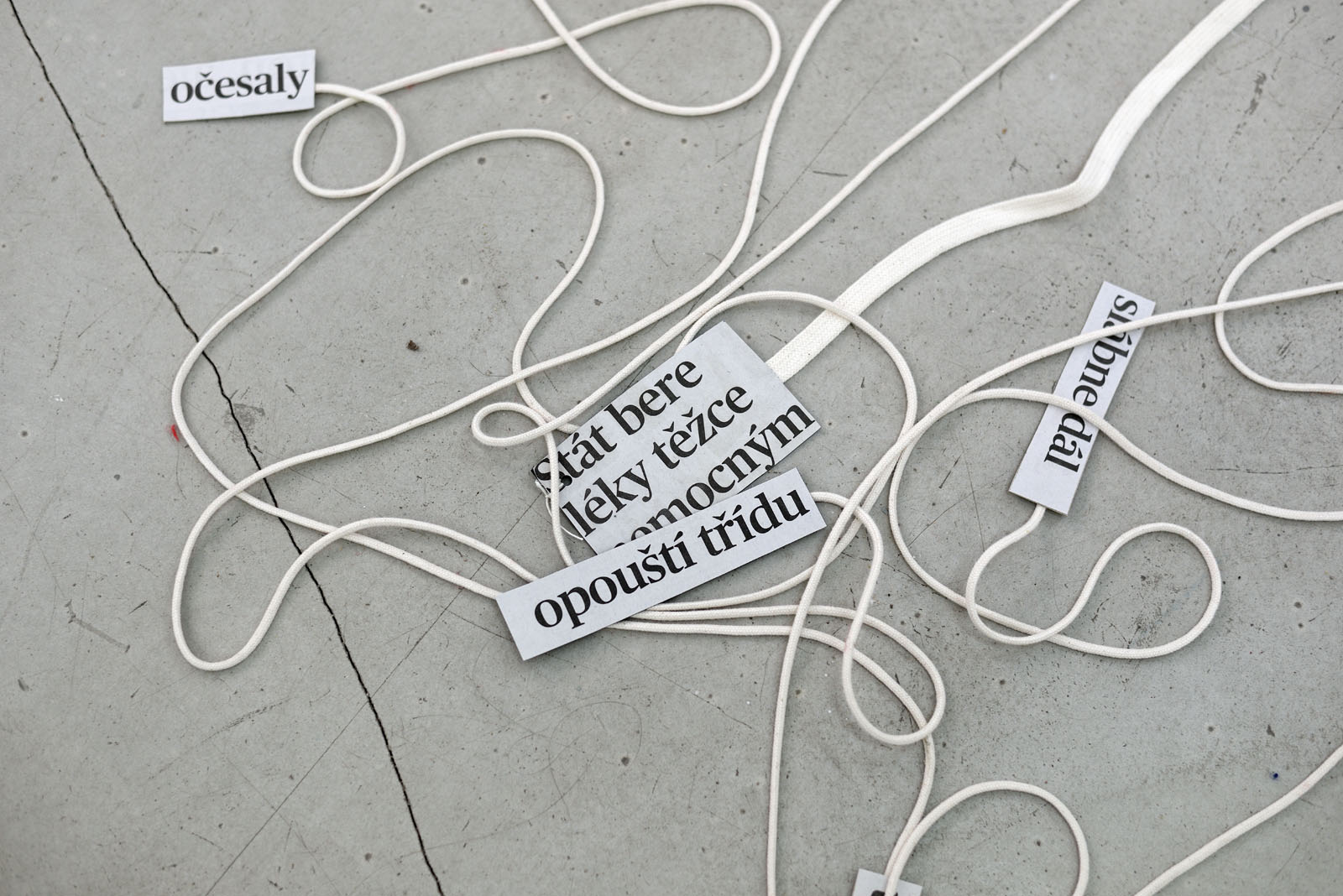

There is another moment which connects the work of both Evas. The cuttings of daily news, which in its own way characterizes a woman, one who is cutting out information but also labels the world which generates this news, has a representational and performative format similar to the Box of Miracles. Beyond the performative part, Eva Koťátková’s woman in the exhibition, eventhough she has other props, is mainly represented by these strips of paper with text, newspaper cutouts that were also, by the way, sent out in the exhibition announcement. Whoever knows Eva Koťátková personally knows that when she visits someone she brings with her paper and pictures that she has cut out in her free time. The individual collages are not random, however. There is always something personal glued into them which is connected to us. Cutting out and then folding, layering and gluing was important for the folding and unfolding of the world mainly in the late work of Eva Kmentová. It would maybe be an oversimplification to say that paper is an easier material for work in difficult, restrictive times, even though that was probably the case. But paper is also the disembodying gesture of a sculptor who has already investigated a large part of the cement and plaster world and with her own imprint perhaps wanted to explore other constructions and compositions. The blue printing color that Kmentová used to color paper with, which she then cut out into the richly associative shapes of fingers, clouds and raindrops, refers to the printing of text, and to something between picture and text, to the conceptual, but also to folk traditions. The subjects which are connected in these collages associate the world of fingers, plants, shrubs, rib cages, smoke, water and clouds that are one unbreakable whole, one body.

Eva Koťátková, on the other hand, chooses the idea of bodily separation to express something similar. She creates a picture of our time which thoroughly separates all bodies, scientific and societal branches and activities into separate units. The intelligence of an octopus, the number of their grasping limbs, which are for many contemporary theoreticians of the anthropogenic and chthulucenic a symbol of decentralized thought and could be fantasized as a way to help us connect the individual parts of the organism to one other without the hierarchical institutions of executive power. The woman who has settled herself in the head of the octopus is testing how an organism feels when it thinks with its whole body. The theatrical audience enters into the octopus’s tentacles and tests the same. The tentacles and tubes through which information flows could mutually interconnect us. This kind of thinking is perhaps a more hopeful idea about the healing powers of humanity as opposed to the number of support apparatuses and mechanisms that are only temporarily useful and divide people into those who are inside and outside, healthy and ill, into those that hold on, and those who have nothing to hold on to, as reflected in Eva Koťátková’s installation.

In conclusion, I would very much like to thank, on behalf of all of us, Polana Bregantová, not only for her generous loan of most of Eva Kmentová’s works seen here in the exhibition, but above all for the kind and informative meetings during the preparation of the exhibition.

Edith Jeřabková, September 2018