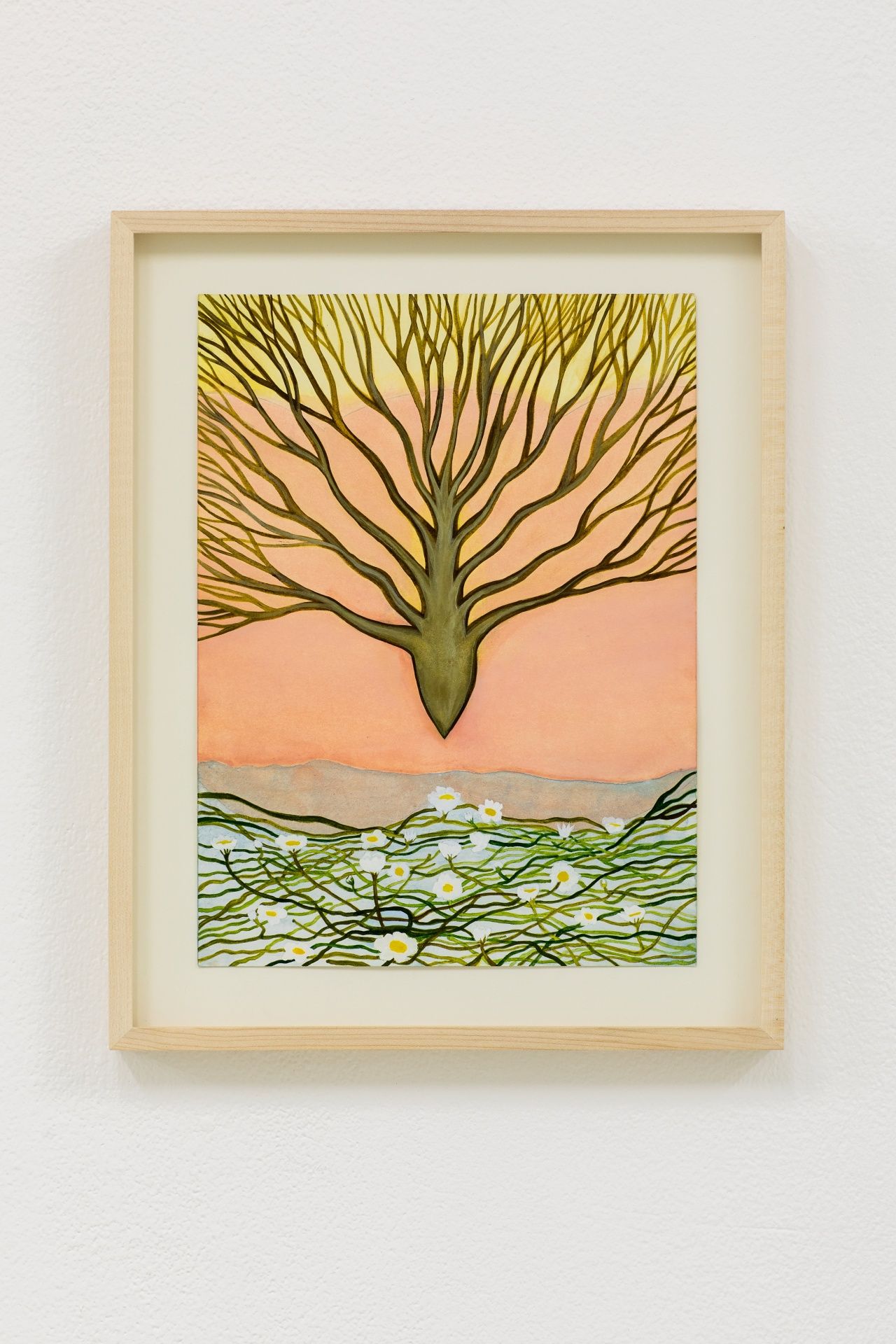

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2022, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

Leaking Sounds, 2022/24, glass. crocheted wool and embroidery, 128x73x30cm

Leaking Sounds, 2022/24 (detail)

Leaking Sounds, 2022/24 (detail)

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

from the series Wet Scores for Listening, 2024, watercolor pastel on paper, 29.7x21cm

Leaking Sounds, 2024, crocheted wool and embroidery, 250x113cm

Leaking Sounds, 2024, crocheted wool and embroidery (detail)