VOGL: KLÁRA HOSNEDLOVÁ AND LUCIA SCERANKOVÁ

5|11|- 17|12|2016

hunt kastner is pleased to present VOGL, a cooperative exhibition project and initiative by Klára Hosnedlová, in the role of artist and fashion designer; Lucia Sceranková, as photographer and book author; Igor Hosnedl, as exhibition architect; and Anymade Studio as graphic designers. The artists and their model entered the home of Dr. Vogl in Pilsen to explore modernism, not through a conceptual lens or as social critique, but rather to experience and delve into the materiality of the times and interiors of Adolf Loos.

Most of us have experienced, or are still experiencing, the role of inhabitant of an apartment, or house, that we have inherited from our ancestors, or rented from strangers. And many of us have created a direct link to modernism through second-hand, period furniture and objects in our rented dwellings. Entering a historic apartment as a temporary occupant forces a person to think about their predecessors, who set up the home. This connection with the past, through specific objects or through the space we inhabit, is expressed in this collaborative project by the artists – they are interested in what continues to attract the youngest generation to the modern past.

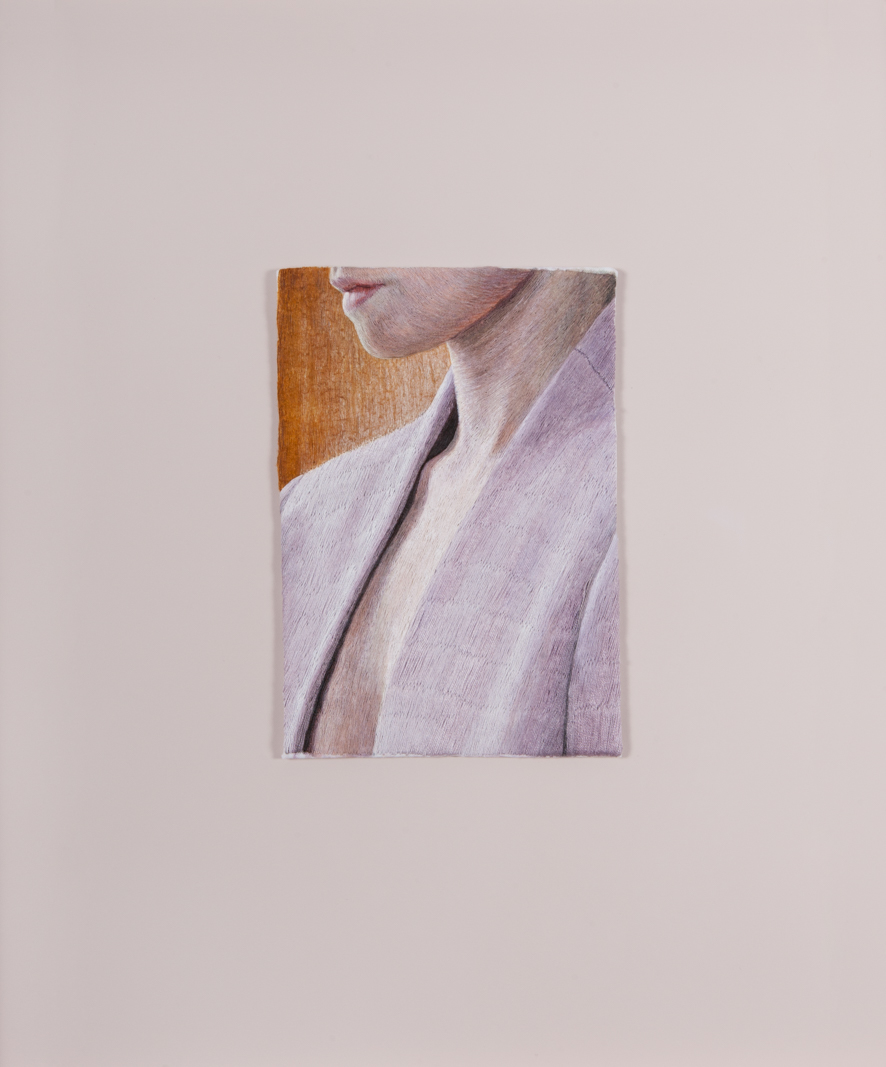

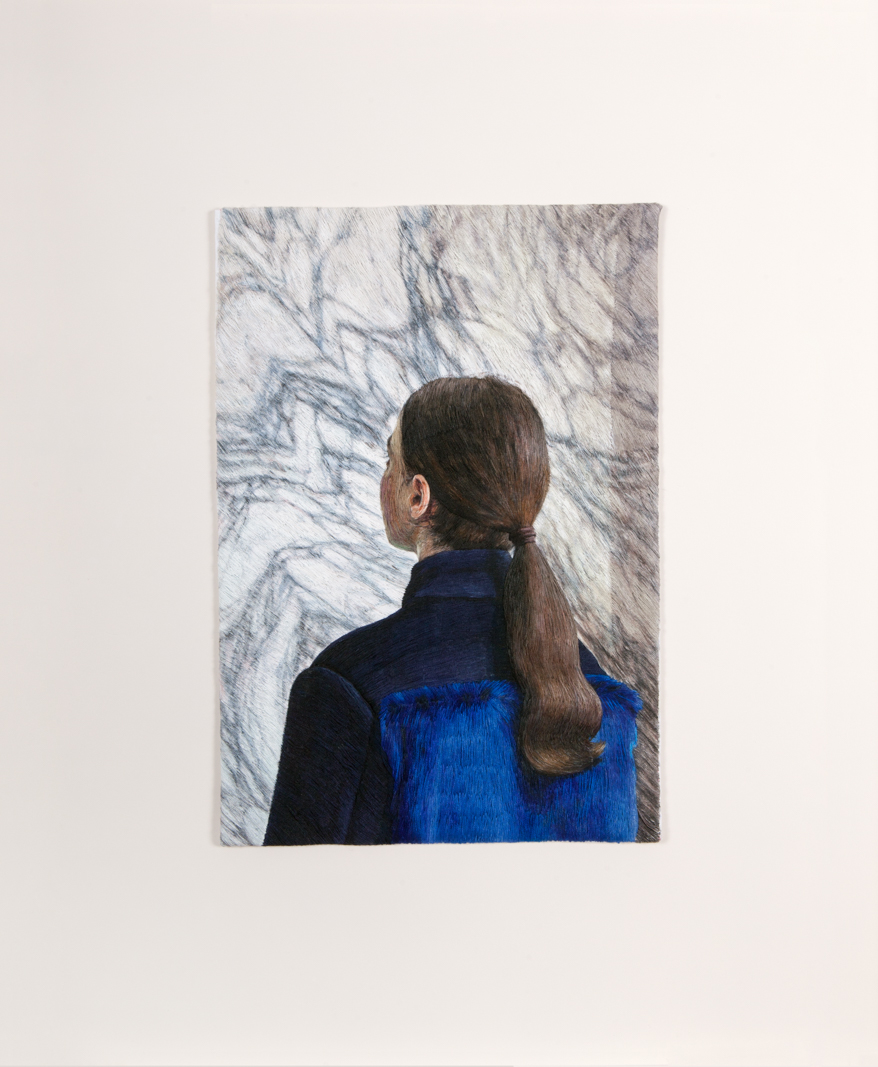

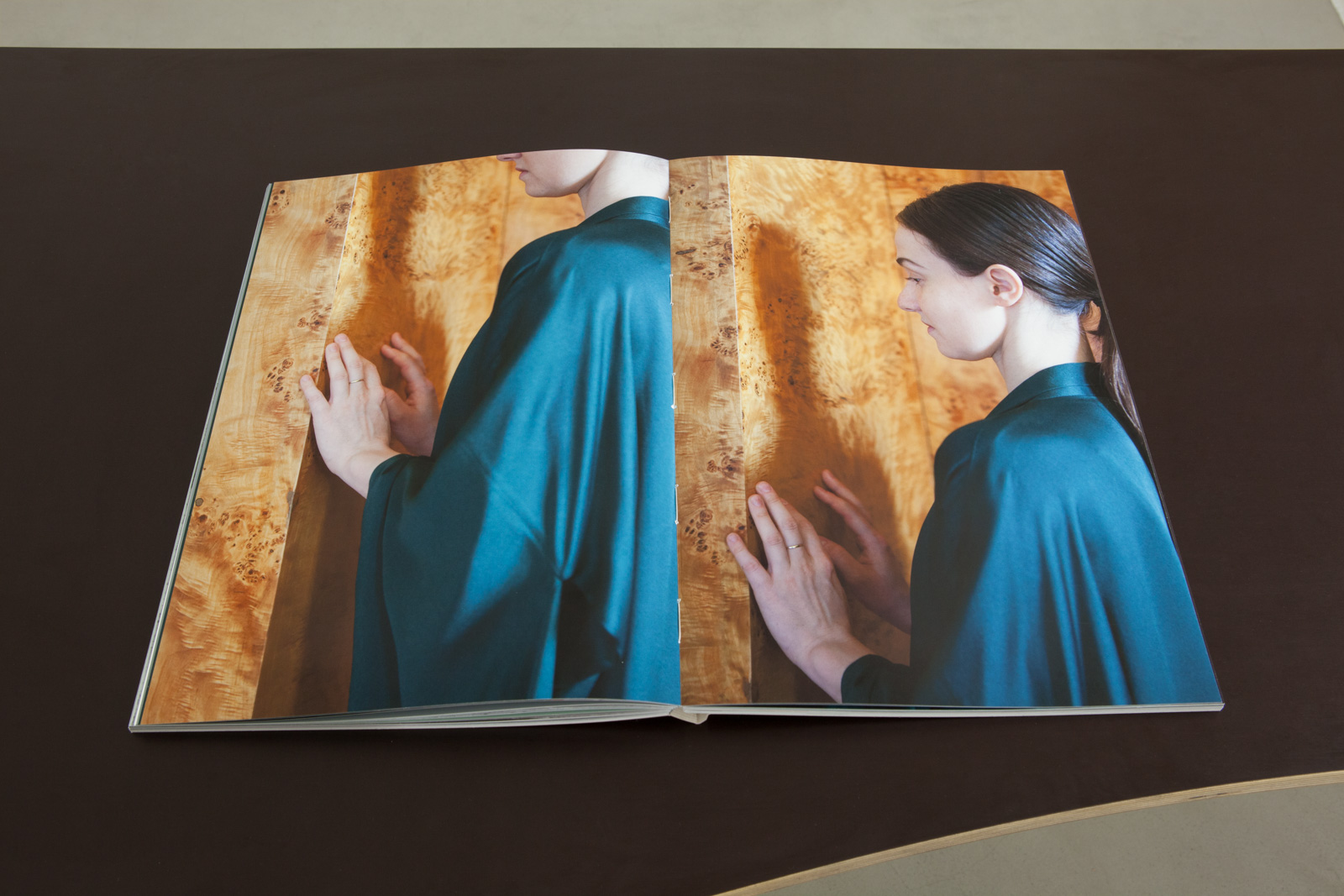

This project revolves around the character of a young woman who moves throughout the apartment of Dr. Vogl as a nymfa moderna, not as an inhabitant but, rather, attentively and perceptively, as a being from another time and perhaps even another space, as if she wanted to blend in with the environment and era when Adolf Loos was designing apartments for the wealthy citizens of Pilsen. Through the use of clothing modeled by the young woman and designed by Hosnedlová, modernistic interpretations of the current century penetrate into the 1930s. Doctor Vogl’s apartment and Loos’ other interiors which are visited by the trio appear to have an encounter with the future. Positions from the past and present permeate one another – the materiality of the ‘30s as well as some of the functionalist genius’ formal solutions enter into Hosnedlová’s embroidery, while contemporary expression, along with postmodern moments and references, creep into the preserved Pilsen apartments.

The most noticeable aspect is the link between Loos’ architectonic solutions and the medium of traditional embroidery, stereotypically associated with the idea of women’s work. In this case, Hosnedlová quite persuasively enters into the functionalistic canon, and what is more, she does so in a realistic style and with almost decadently symbolist expressions. The artist looks at Loos’ creations with respect and admiration, all the while not allowing this to put boundaries on her creative expression. The accent on traditional women’s work within the framework of modern architecture (which, because of its functional nature, would tend to emphasize industrial aims) is further reinforced by the female protagonist of Hosnedlová’s embroidery and Lucia Sceranková’s photography. This single and ever-repeating character of the young woman at first seems to potentially problematize Loos’ relationship with women but, in effect, imprints the progressivism of a woman’s sense for enduring values and forms upon the modernist conception – through her opinions, work and interests. Female sensuality and the everyday experience of family and work are set against the merciless logic of function.

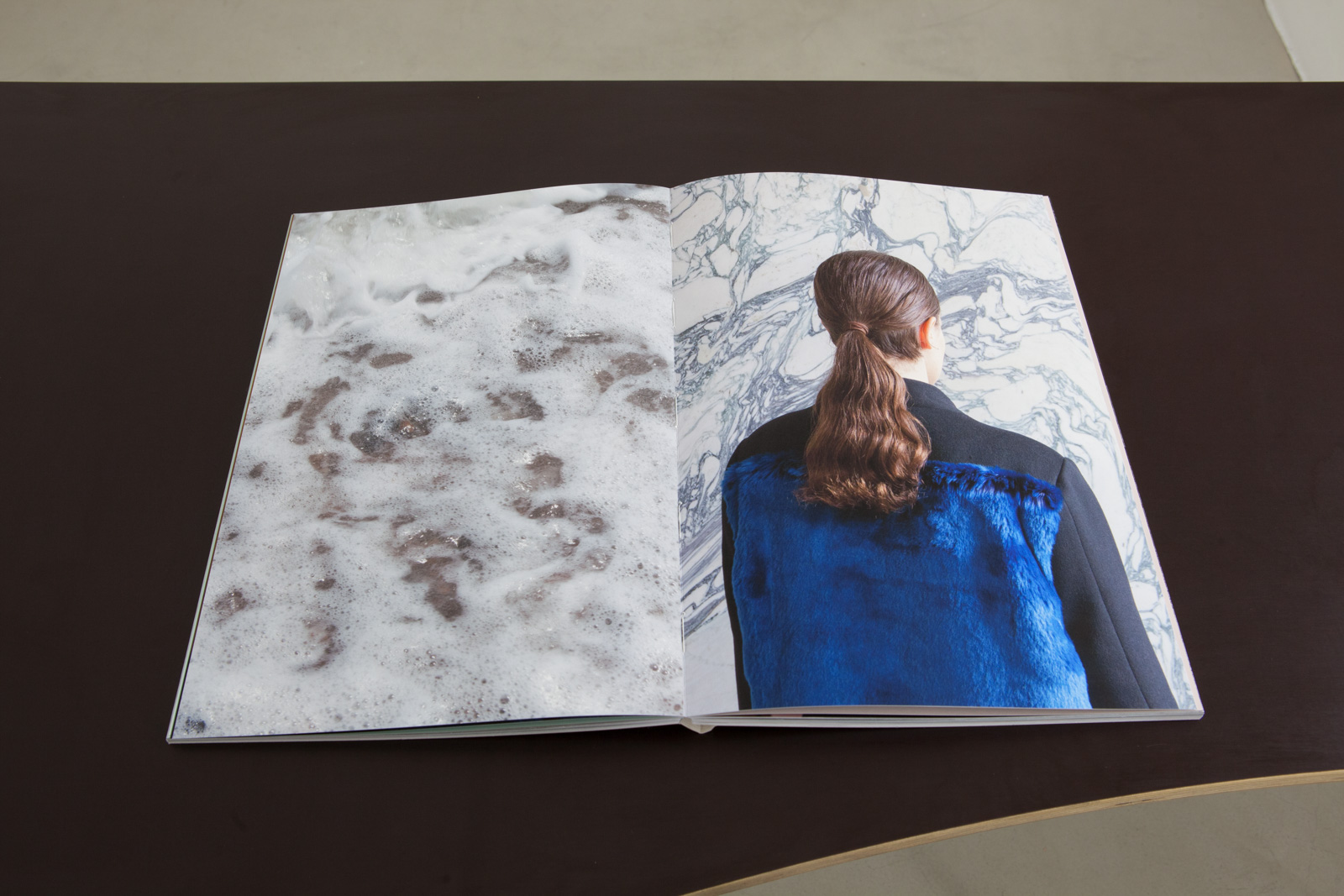

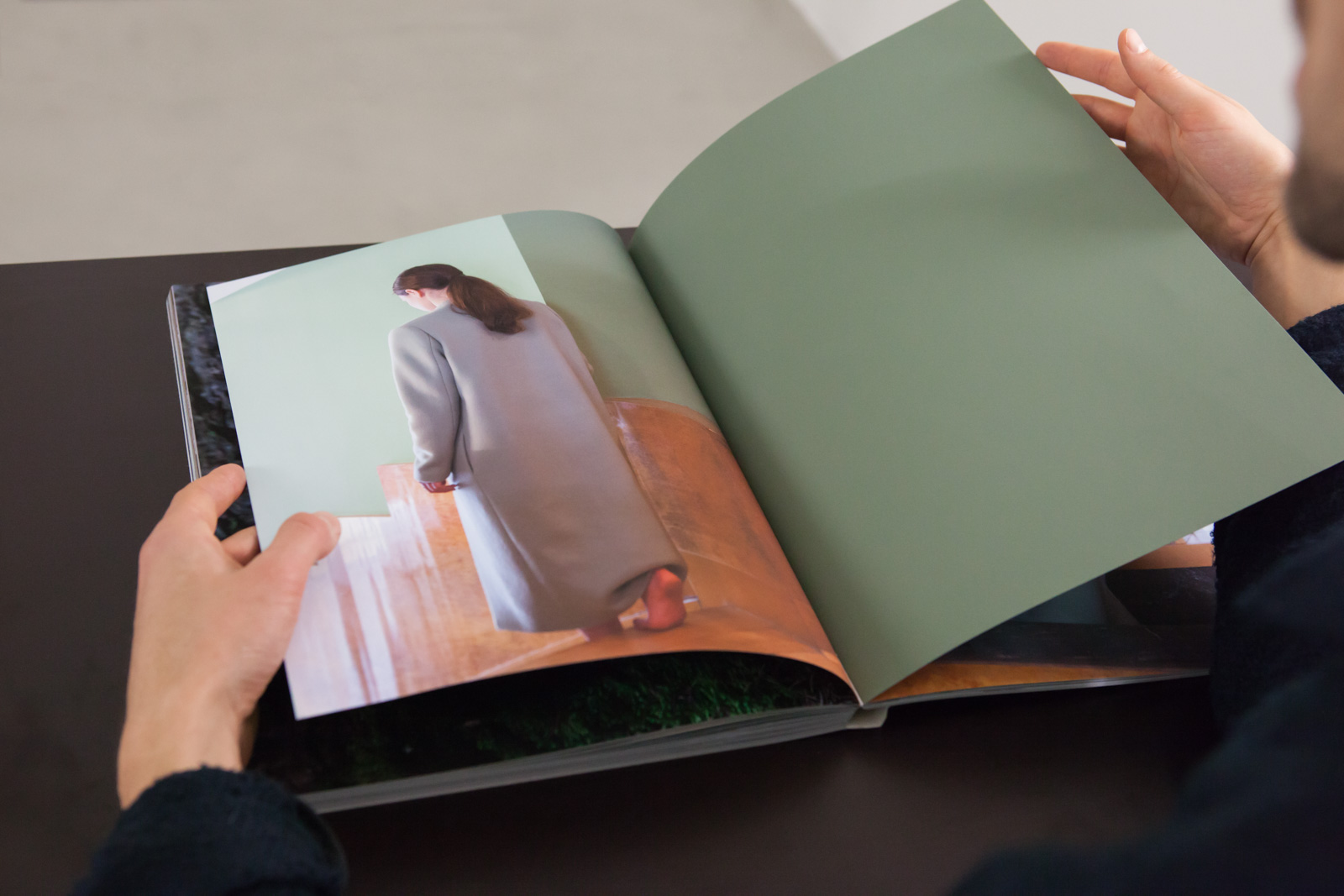

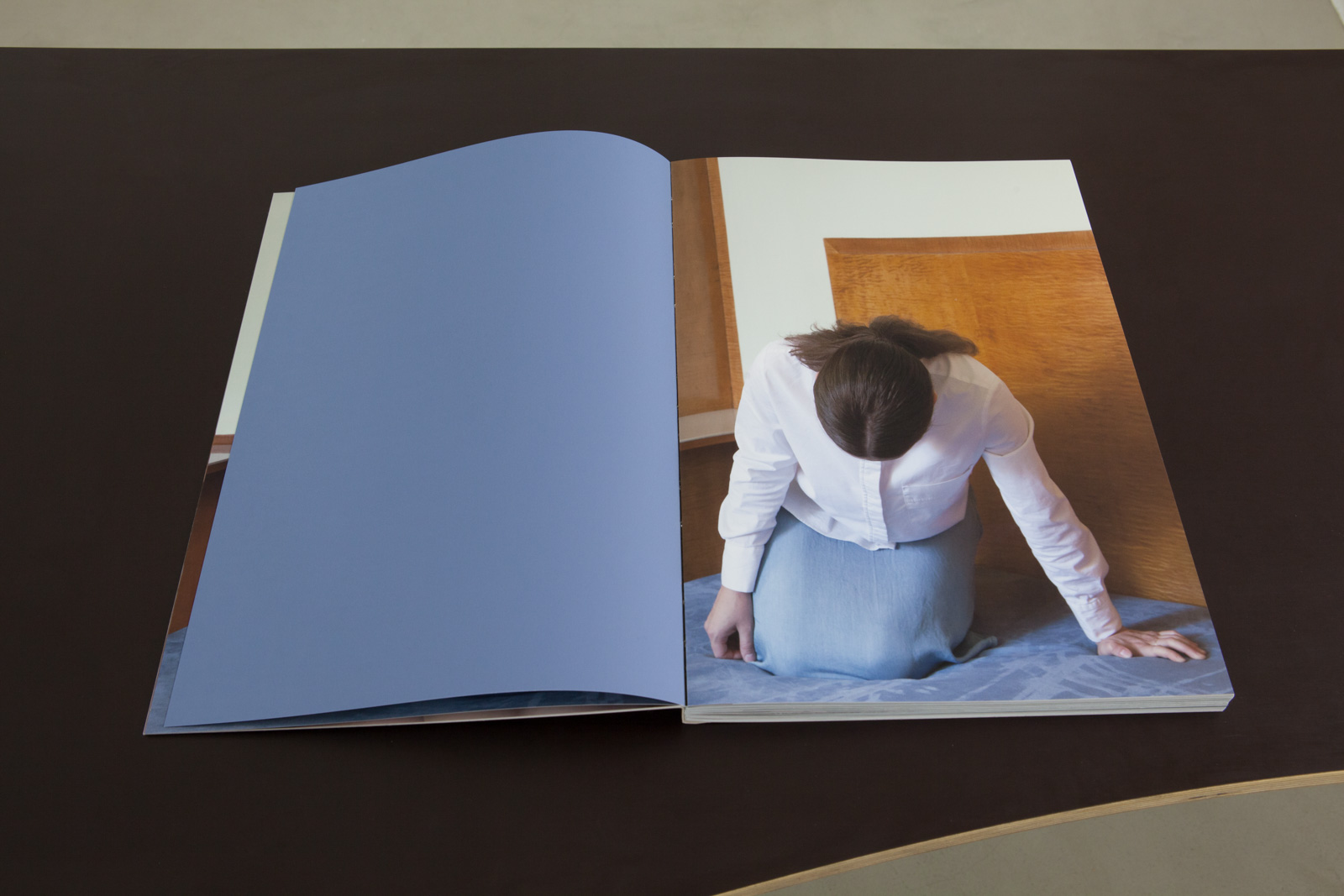

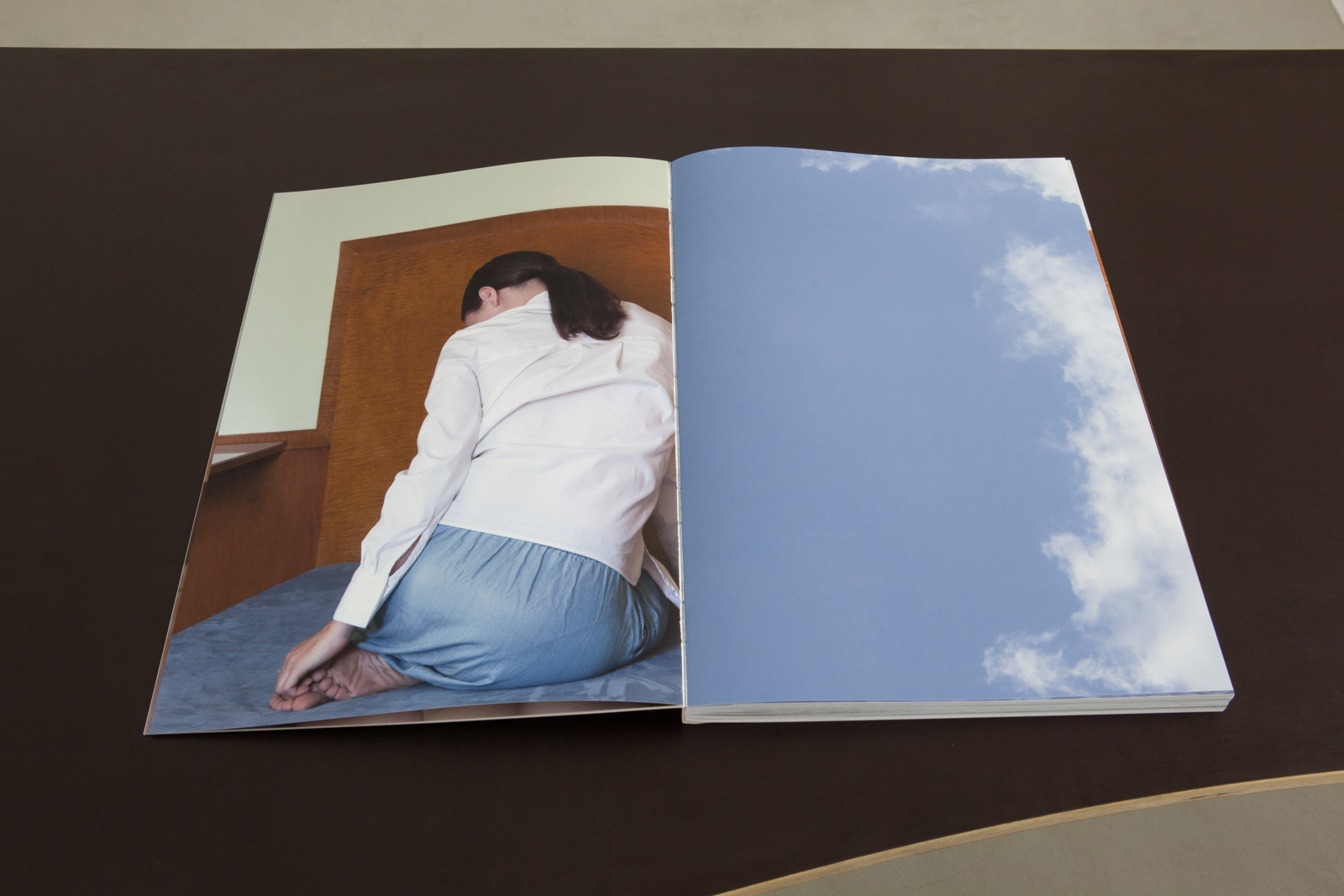

Lucia Sceranková, who Klára Hosnedlová invited to cooperate on this project, photographs arranged situations in several of Loos’ apartments, both as documentation for Hosnedlová’s embroidery and also for her independent creative expression presented at the exhibition as an artist’s book. Sceranková´s book of photographs will be presented as a jewel in the intellectual household, surrounded by its particular aura and placed in the imaginary interior of an apartment at hunt kastner. The book contains no text, refusing the hegemony of words and choosing, instead, the images and their motifs. It does not attempt to surprise with originality, citations and unexpected turns but rather, tries to capture transient states, continuity, mental and spatial connections and collective authorship. The book consists of three pictorial genres. It is dominated by views of the interiors, where our attention focuses on the details of the materials (stone, wood, metal, mirror, fabric), on the girl’s clothing and the beauty of the human form, casting a certain liveliness onto Loos’ canon of architectonic designs. Other views make absolute the colors captured from various materials in the apartment, as well as from the woman’s clothing and skin tone, thus creating a photographic picture purely of color and tone. The third component comprises a view into nature itself, an ornament that Loos allows and the basis for materiality in Loos’ interiors, which, on this level, maintains the intertwined state of modern man/woman with nature, even if transferred into the artificial world of the dwelling.

For the exhibiting artists, working with such loaded themes as modernity and Loos’ creations (practically and theoretically) was a great challenge. Their work does not want to be mere commentary, a substitute for theoretical investigations in artistic research or the simple intervention of the present into the past. They are not looking for historical or mental anchors in modernity; this has already been done by the previous generation – rather, they want to re-enter into that cultural layer and look for connections not on a conceptual, but on a material level. Both artists and the architect of the exhibition, Igor Hosnedl, want to communicate the material quality of things, the surfaces of objects, composition, and color through the material language of functionalism. For this, direct experience with the environment is absolutely essential, and so all three of them not only enter the apartment of Doctor Vogl, but also study and work there and in other apartments in Pilsen designed by Loos. Loos’ designs of apartment interiors in Pilsen has recently gained greater attention and not only from specialists and restaurateurs. From a relatively large number of realizations in Plzen, only four apartments are still preserved today (the homes of MUDr. Josef Vogl, Vilém and Getruda Kraus, Jan Brummel, and Ing. Oskar and Jana Semler.) The ‘occupation’ of Vogl’s apartment by these contemporary artists is symbolic, and the art was made with careful attention to the heritage of Adolf Loos, while at the same time with confidence in the gestures of contemporary art. This collaborative project wants, among other things, to draw our attention to the impossibility of individual perceptions of modern architecture and art, which – in order to survive – needs to be preserved and ‘institutionalized’ in the context of a museum or gallery.

Klára Hosnedlová (for whom art, fashion, design, craft, and lifestyle are means of probing into individual areas of social life and history) has attempted, with her colleagues, to cross the border of the unexplored and highlight an emotional understanding of the work. For her, art is where this overlap can take place and where one can encounter various layers of time. In her creative thinking, the author confronts Loos’ famous theory on the crime of ornament. His iconic essay relates to the dilemma of contemporary art, especially in our context as a former Eastern bloc country, which has gone through a period of so-called post-conceptual development, weakening the formal and ornamental components of artwork. Today’s art, however, is overcoming this tendency and is now admitting ornament with an animated and sometimes even revolutionary force. This is likewise the case with form, material and technique – all of these areas in contemporary art theory are being given unprecedented attention. Following the crash of the ‘virtual’ transactions in the banking sector, not only economists, but artists too, are putting their trust more in a material foundation and are investigating its potential.

The artists’ interest in the modernist heritage is also entering into this development. Klára Hosnedlová and Lucia Sceranková freely move within this period and, while enchanted by Loos’ objects, materials, shapes and spaces, retain an analytical eye. It is certainly no mere coincidence that the authors not only allow a female character into the apartments designed by a master, but also bring in traditional women’s work. They do so, however, not only with a certain mastery of their own creative approaches, but also with an admitted femininity, which in our environment, still unable to appreciate the nuances of feminist approaches, is a relatively rare position on the Czech art scene.

Adolf Loos’ work is reflected in theirs, not only as an environment for the photographs of Sceranková and the documentation and installation of works of Hosnedlová, but has been an integral partner from the project’s inception. The physical spaces are not widely depicted in the photographs, the artists choosing to focus on the model, materiality and surface details, letting Loos’ interior speak through the mental and sensual dispositions of the model.

As for the architectural contribution to the project – Igor Hosnedl’s approach and consideration of the iconic forms of functionalist architecture are not mere expression or a kind of translation of historicism into the present, but significantly departs from Loos in taking down the hierarchical order between fine arts, applied arts and design. This is also why all the authors decided not to undermine the status of the gallery, while still preserving several elements of apartment culture, so that both environments, the gallery and the apartment, would meld into the free form of a new and independent artistic work.

An equally significant component of the exhibition is the idea of a showroom, in which a fashion designer’s new clothing collection is being sold. Lucia Sceranková’s book also contributes to this aspect in its approximation to a lifestyle magazine. Built upon these three readings of the space, in which no one reading is dominant, is the already mentioned wiping away of the border between fine and applied art, which is underlined by the inclusion of work by the graphic design studio Anymade. This reminds us, immediately upon entering, how lifestyle forms contemporary art and architecture, and how it was a very important area of interest for Loos. Anymade’s contribution is not a subservient element of the exhibition project and takes on an active life of its own – a symbiosis occurring automatically between fine art and things in ordinary life when not encumbered by the evaluation criteria of institutional apparatuses.

Edith Jeřabková, October 2016